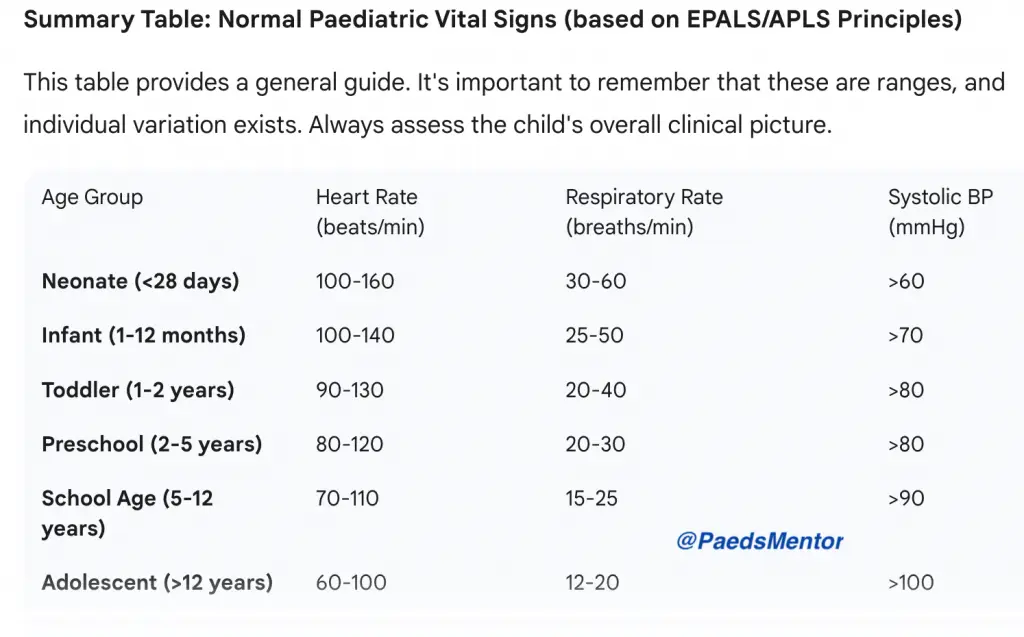

Normal range for Paediatric HR, RR & BP

Paediatric Vital Signs

Have you wondered why are paediatric vital signs different?

Remember physiological differences:

Children are not just “small adults.” Their physiology is unique and changes rapidly with age.

Higher metabolic rate, leading to faster heart and respiratory rates.

Less cardiovascular reserve; they compensate well for a long time before suddenly “crashing.” This means early signs of deterioration are subtle.

Blood pressure is a late sign of shock. A child can be in severe shock with a normal or even high blood pressure due to powerful vasoconstriction.

Vital signs are a key part of the structured ABCDE approach (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure). They provide crucial information for assessing a child’s clinical state and identifying a deteriorating patient:

Heart Rate (HR):

Normal ranges: HR is age-dependent and declines with increasing age.

Clinical relevance: A persistently high or low HR is a red flag.

Tachycardia: A common and often early sign of illness, stress, pain, or fever. It’s the body’s primary compensatory mechanism for reduced cardiac output. A high HR in a well-appearing child might be due to a simple cause, but in an unwell child, it’s a critical sign of shock or hypoxia.

Bradycardia: A very concerning sign in a sick child. It is often a pre-terminal event, particularly in infants, as it is usually caused by profound hypoxia. This requires immediate action.

Respiratory Rate (RR):

Normal ranges: Like HR, RR is age-dependent and decreases as the child gets older.

Clinical relevance: The respiratory system is the most common cause of cardiac arrest in children.

Tachypnoea: The most sensitive and often earliest indicator of a child in respiratory distress or shock.

Respiratory effort: It’s not just about the rate. Trainees must also assess for signs of increased work of breathing (e.g., nasal flaring, tracheal tug, chest wall recession, grunting). These are vital signs in their own right and indicate respiratory compromise.

Blood Pressure (BP):

Normal ranges: The lower limit of systolic BP is approximately 70 mmHg + (2 x age in years). This is a simple but critical formula for quick bedside assessment. Note: a child can be in shock with a normal BP.

Clinical relevance: As mentioned, hypotension (low BP) is a late and ominous sign of decompensated shock in a child. By the time a child’s BP drops, they have exhausted their compensatory mechanisms and are at high risk of cardiac arrest. The focus should be on recognising and treating signs of compensated shock (e.g., tachycardia, cool peripheries, prolonged capillary refill time) before BP falls.

Temperature (Temp):

Normal range: A normal core temperature is approximately 36.5°C to 37.5°C.

Clinical relevance:

Fever: A common cause of tachycardia and tachypnoea, but it can also be the first sign of a serious infection.

Hypothermia: A significant risk factor for deterioration, especially in infants. It can lead to bradycardia, hypovolaemia, and coagulopathy.

Capillary Refill Time (CRT):

Normal range: Less than 2 seconds.

Clinical relevance: A prolonged CRT is a key indicator of poor peripheral perfusion and compensated shock. It is an essential component of the EPALS circulation assessment.

Level of Consciousness:

Assessment: Use the AVPU scale (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive) or the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) for older children.

Clinical relevance: Altered mental status can be due to hypoxia, shock, or neurological causes. It is a critical sign of a sick child.

Paediatric Early Warning Scores (PEWS):

Explain the concept of PEWS systems, which standardise the assessment of vital signs and trigger a clear, escalating response to a deteriorating child. They are based on the age-related vital sign ranges.