Syncope in Children

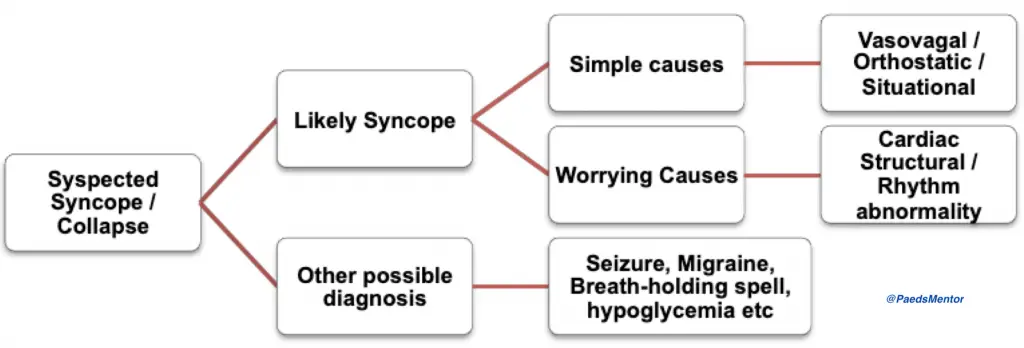

Syncope, or fainting, is a brief, transient loss of consciousness caused by a temporary reduction in blood flow to the brain. In children, syncope is usually benign, but it’s crucial to differentiate a simple faint from more serious cardiac or neurological causes.

The UK approach, as outlined by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), emphasizes a thorough history, physical examination, and a 12-lead ECG as the cornerstone of assessment.

Causes of Syncope

Syncope can be broadly classified into simple (benign) and more worrying (pathological) causes.

Simple (Benign) Causes

Vasovagal Syncope: This is the most common type and is triggered by emotional distress, pain, anxiety, or prolonged standing in a warm environment. It’s often preceded by a prodrome of nausea, sweating, lightheadedness, and pallor.

Orthostatic Hypotension: This occurs when there’s a significant drop in blood pressure upon standing. It can be caused by dehydration, illness, or certain medications, such as those for ADHD.

Situational Syncope: This is a type of vasovagal syncope brought on by specific triggers like coughing, urination, or defecation.

Worrying (Pathological) Causes

Cardiac Causes: These are more serious and can be due to structural heart problems or arrhythmias.

Structural: Examples include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) or aortic stenosis.

Arrhythmic: These can be life-threatening and include conditions like Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, long QT syndrome, or ventricular tachycardia (VT).

Neurological Causes: While less common, syncope can be a manifestation of a seizure, although this is more likely to be a different entity (epilepsy).

History

The history is the most important part of the assessment.

Event Details: Ask a witness to describe the sequence of events before, during, and after the episode. Was there a prodrome? Did the child have any stiffness or jerking movements?

Contributory Factors: Identify any potential triggers.

Associated Symptoms: Ask about chest pain, palpitations, or breathlessness, as these are significant red flags.

Past Medical History: Enquire about any known cardiac or neurological problems.

Family History: A family history of sudden cardiac death, early death, or known arrhythmias is a major red flag.

Medications: Check for any medications that can affect blood pressure or the QT interval.

Examination

Vital Signs: Check the child’s pulse rate and rhythm. Also, perform an orthostatic BP check (lying and standing) to look for a drop in pressure.

Cardiac and Neurological Exam: A focused examination should be performed to look for signs of structural heart disease or neurological issues.

Red Flags:

Syncope during or after exercise.

Syncope with no warning or prodrome.

Associated chest pain or palpitations.

A family history of sudden cardiac death or arrhythmias.

Investigations

A 12-lead ECG is mandatory for any child with syncope. It can help identify the most serious underlying causes.

Key ECG Changes to look for

PR Interval: Look for a short PR interval with a delta wave (suggesting WPW syndrome) or a prolonged PR interval (suggesting a heart block).

QTc Interval: A prolonged QTc interval is a red flag for long QT syndrome.

QRS Complex: Look for a wide QRS complex or signs of ventricular pre-excitation.

T Waves: Inverted or flattened T waves can suggest myocardial issues like myocarditis.

Specialist Investigations

Holter ECG: A 24-hour continuous ECG can be used to capture intermittent arrhythmias.

Echocardiogram (ECHO): An ultrasound of the heart to look for structural abnormalities like HCM.

Exercise ECG: A stress test can unmask arrhythmias that only occur during exertion.

Tilt-Table Testing: Used to confirm a diagnosis of vasovagal syncope in ambiguous cases.

Management strategies for syncope in children are primarily determined by the cause, with a focus on distinguishing between benign and serious conditions. The majority of cases are simple faints that can be managed with reassurance and lifestyle advice, while a small subset requires specialist cardiology referral.

Management of Simple Syncope

Simple syncope, such as vasovagal or orthostatic syncope, is benign and does not require medication. The key is to empower the child and family with knowledge and self-management techniques.

Reassurance and Explanation: The first step is to explain that the faint is a normal physiological response, not a sign of a serious disease. This helps to reduce anxiety, which can be a trigger for future episodes.

Lifestyle Advice:

Hydration: Advise the child to maintain good fluid intake.

Diet: Encourage them to not skip meals and to have an adequate salt intake.

Avoidance of Triggers: Identify and avoid triggers such as prolonged standing, warm environments, or emotional stress.

Self-Management: Teach the child to recognize the warning signs (prodrome) like lightheadedness, nausea, or sweating. At the onset of these symptoms, they should immediately sit or lie down to prevent the faint and avoid injury from a fall.

When to Refer to Paediatric Cardiology

Referral to a specialist is crucial when there are red flags that suggest a more serious, underlying cause.

Syncope During or After Exercise: Any loss of consciousness during or immediately after physical exertion is a major red flag and warrants urgent cardiology referral.

Associated Symptoms: Syncope accompanied by palpitations or chest pain is highly concerning and needs specialist investigation.

Lack of Prodrome: A faint that occurs without any warning signs, or a sudden and unexpected loss of consciousness, is a red flag for a cardiac arrhythmia.

Known Cardiac History: A child with a pre-existing cardiac condition who experiences syncope should be referred for a full cardiology review.

Family History: A family history of sudden cardiac death, early death, or known arrhythmias is a significant risk factor and indicates the need for specialist evaluation.

ECG Abnormalities: Any abnormal findings on a 12-lead ECG, such as a prolonged QTc interval, a short PR interval with a delta wave (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome), or signs of ventricular hypertrophy, necessitate an immediate cardiology referral.

Specialist Investigations and Medication

Investigations:

Holter Monitor: A 24-hour continuous ECG to capture infrequent arrhythmias that may not be present during a standard ECG.

Echocardiogram (ECHO): An ultrasound of the heart to evaluate for structural abnormalities like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Exercise ECG: A stress test can be used to unmask arrhythmias that are triggered by physical activity.

Medication: Medication is not used for simple syncope. It is reserved for children with a confirmed pathological cause of syncope, such as an arrhythmia or structural heart disease, and is prescribed by a paediatric cardiologist.

In summary, the majority of paediatric syncope cases are managed conservatively. The key is to be vigilant for red flags that necessitate a specialist referral to rule out life-threatening conditions.