Neck Lumps in Children

In the UK, the approach to a neck lump in a child is based on a structured clinical assessment to differentiate common, benign causes from rare but serious conditions like malignancy or deep-seated infection. Recent guidance from sources like NICE and the UK Sepsis Trust emphasizes a high index of suspicion for “red flags” and the importance of appropriate, not excessive, investigation.

Differential Diagnosis

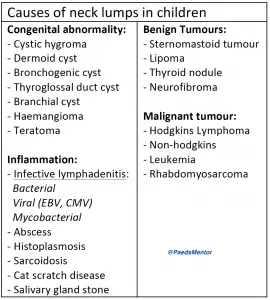

Neck lumps in children can be broadly categorised by their aetiology.

Infective/Inflammatory (Most Common):

Reactive Lymphadenopathy: The most frequent cause. Nodes enlarge in response to a viral or bacterial infection (e.g., URTI, tonsillitis, dental abscess). They are typically small, mobile, bilateral and non-tender.

Bacterial Lymphadenitis: An acute infection of the lymph node itself. The node is often larger, tender, warm, and the overlying skin may be red. It can progress to an abscess.

Atypical Infections: Consider these for persistent, non-tender, or unusual lumps:

Cat Scratch Disease (Bartonella henselae): A history of cat exposure is key. The lump is usually a single, tender lymph node, often in the neck or axilla.

Tuberculosis (TB): The lump is usually non-tender and firm. A history of exposure to TB is important.

Atypical Mycobacterial Infections: This is an increasingly recognised cause of chronic, non-tender neck lumps in young children, which often present with a violaceous (purplish) hue to the overlying skin.

Congenital – These lumps are present at birth but may not become clinically apparent until later in childhood. They arise from embryonic remnants or developmental anomalies.

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst: This is the most common congenital neck lump. It arises from the remnant of the thyroglossal duct, which is the path of the thyroid gland’s embryonic descent. It is a midline lump that characteristically moves upwards when the child swallows or protrudes their tongue. * Branchial Cleft Cyst: These are typically found on the side of the neck, often in the anterior cervical triangle. They are remnants of the branchial arches from embryonic development. They can present as a cyst, a sinus, or a fistula and may become infected, leading to an acute inflammatory presentation.

Dermoid Cyst: These are benign cysts that form from misplaced ectodermal cells during embryonic development. They are usually found in the midline and may contain hair follicles, sweat glands, and other skin tissue.

Vascular Malformations: These are abnormal collections of blood vessels (e.g., lymphatic malformations, haemangiomas). They are present at birth but may not be noticed until they grow. Haemangiomas are often not visible at birth but grow rapidly in the first few weeks of life, while lymphatic malformations are present at birth.

Malignancy (Rare, but important to rule out):

Lymphoma: The most common type of neck malignancy in children. The lumps are typically firm, non-tender, and may be matted together. Associated “B symptoms” (fever, night sweats, and weight loss) are highly suggestive.

Leukaemia: Cervical lymphadenopathy can be a presenting feature. A full systemic examination for other signs, such as pallor, bruising, or hepatosplenomegaly, is crucial.

Neuroblastoma: A solid tumour that can present in the neck, especially in infants and young children.

Thyroid Cancer: A rare cause, which presents as a lump in the thyroid gland that moves with swallowing.

History and Examination

The focus is on identifying red flags that suggest a more serious cause.

History:

Time Course: A lump that has been present for less than 2 weeks is most likely infective. A lump that persists for more than 4-6 weeks warrants further investigation.

Associated Symptoms: Ask about fever, weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue (known as “B symptoms,” a key sign of malignancy).

Risk Factors: Consider recent cat exposure, TB contact, or a family history of cancer.

Examination:

Location: Supraclavicular lymph nodes are highly suspicious for malignancy. A lump that moves with tongue protrusion or swallowing is likely a thyroglossal cyst.

Size: UK guidelines generally consider a size of > 2 cm concerning, especially if it’s persistent and non-tender.

Consistency: A lump that is hard, fixed, and “rubbery” is more concerning than a soft, mobile lump.

Systemic Exam: Look for other enlarged lymph nodes (generalised lymphadenopathy), hepatosplenomegaly, pallor, or bruising, which may indicate a haematological malignancy.

Red Flags

Urgent referral to paediatrics or ENT is indicated if a child presents with:

Airway Compromise: Stridor, drooling, or difficulty swallowing.

Systemic Illness: The child appears unwell with a high fever or signs of sepsis.

Rapidly Enlarging Mass: Especially without signs of acute infection.

Suspicious Features:

A lump that is > 2 cm and is persistent or growing.

A supraclavicular lump, regardless of size.

A lump that is hard, fixed to underlying structures, or matted.

Presence of “B symptoms” (unexplained weight loss, night sweats, or fever).

Signs of haematological malignancy, such as pallor, bruising, or petechiae.

Investigations and Management

The approach to investigation and management is a step-wise process guided by the clinical picture.

Initial Management: For a well child with a likely infective lymphadenitis, a trial of antibiotics (e.g., co-amoxiclav) and a review within 48-72 hours is the standard UK approach.

Imaging:

Ultrasound (USS) is the first-line imaging modality. It can differentiate between a solid mass, a cyst, or a lymph node and can identify an abscess formation.

MRI may be required for more complex lesions or to assess deep neck spaces.

Further Investigations:

Blood tests (FBC, CRP, blood culture) are essential for an unwell child.

Serology for atypical infections (e.g., EBV, CMV, Bartonella) may be considered.

Biopsy: If malignancy is suspected, a biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is often avoided in suspected lymphoma as it may not provide enough tissue for a complete diagnosis. An excision biopsy is often preferred.

Referral:

Urgent referral to ENT is needed for any signs of airway compromise.

An urgent referral via a suspected cancer pathway (e.g., the 2-week wait referral) is crucial if malignancy is suspected.

For an abscess, surgical drainage may be necessary after USS confirmation.

For suspected non-tuberculous mycobacteria, an excision biopsy is the recommended procedure, as incision and drainage can lead to a persistent discharging sinus.