Anion Gap in children

The anion gap (AG) is a calculated value used in blood gas analysis to help determine the cause of metabolic acidosis.

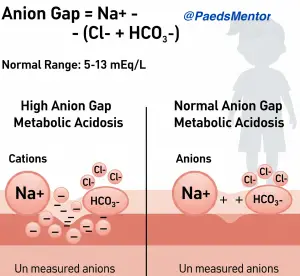

It represents the difference between the main measured cations (positive ions) and the main measured anions (negative ions) in the blood.

Acidosis is certainly ‘metabolic’ if the AG is greater than 30 mmol/L & mostly metabolic of AG >20

In children, it is a crucial tool for a rapid and systematic differential diagnosis of metabolic acidosis, which can be a sign of life-threatening conditions.

Note: Albumin is a major unmeasured anion, and hypoalbuminemia can falsely lower Anion Gap

The Concept and Calculation

The principle of electrochemical neutrality dictates that the total positive charge in the blood must equal the total negative charge. While we measure several key ions, some are not typically measured. The anion gap is the measure of these “unmeasured” anions.

The standard formula for calculating the anion gap is:

AG=[Na+]+[K+]−([Cl−]+[HCO3−]

2. Normal Range

The normal range for the anion gap is 4 to 12 mmol/L.

However, it is important to know that the normal anion gap is largely determined by the concentration of albumin, which is a major unmeasured anion. A low albumin level (hypoalbuminemia), which is common in critically ill children, can falsely lower the anion gap, potentially masking a high anion gap metabolic acidosis.

To correct for this, some clinicians use a corrected anion gap formula: CorrectedAG=MeasuredAG+2.5×(4−Albumin) (where Albumin is in g/dL)

Types of Metabolic Acidosis

The primary purpose of calculating the anion gap is to classify metabolic acidosis into two main categories:

High Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (HAGMA)

This occurs when there is an increase in unmeasured acids in the blood. These acids dissociate, releasing a hydrogen ion (H+), which is buffered by bicarbonate (HCO3−), causing bicarbonate to decrease. The anion part of the acid is “unmeasured,” causing the anion gap to widen.

Common Causes of HAGMA in Children (Mnemonic: MUDPILES)

Methanol: Ingestion of methanol.

Uremia: Renal failure leading to the accumulation of sulfates and phosphates.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA): Accumulation of ketone bodies (beta-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate).

Paraldehyde or Propylene glycol: Ingestion.

Iron or Isoniazid: Overdose. Also includes inborn errors of metabolism, which are more common in children.

Lactic Acidosis: The most common cause of HAGMA in critically ill children, resulting from poor tissue perfusion (shock), hypoxia, or sepsis.

Ethylene glycol (antifreeze): Ingestion.

Salicylates (Aspirin): Overdose.

Normal Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (NAGMA)

This is also known as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. It occurs when there is a loss of bicarbonate (HCO3−) from the body, typically through the kidneys or gastrointestinal tract. To maintain electrochemical neutrality, chloride (Cl−) is reabsorbed to “fill the gap” left by the lost bicarbonate, keeping the anion gap within the normal range.

Common Causes of NAGMA in Children

Diarrhea: The most common cause in children due to the loss of bicarbonate from the stool.

Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA): A group of kidney disorders that impair the kidneys’ ability to excrete acid or reabsorb bicarbonate.

Intestinal Fistula: Drainage of alkaline intestinal contents.

Acetazolamide: A diuretic that causes renal bicarbonate loss.

Rapid Saline Infusion: Can cause acidosis due to the high chloride content of the fluid.

Pitfalls related to the anion gap (AG) in children mostly involve misinterpretation due to confounding factors or a failure to consider age-specific physiology.

Hypoalbuminemia

Hypoalbuminemia is the most common and significant pitfall. Albumin is a major unmeasured anion, so when its concentration is low, it causes a reduction in the normal anion gap. This can lead to a falsely normal AG in a child with a true high anion gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA), delaying a correct diagnosis. This is why it’s crucial to calculate a corrected anion gap if albumin levels are low.

Age-Specific Normal Ranges

While the standard AG range is 4-12 mmol/L for older children and adults, infants, particularly premature infants, have slightly different ranges. Their normal AG can be lower due to a higher ratio of unmeasured cations to anions.

Lactic Acidosis

Lactic acidosis is the most common cause of HAGMA in critically ill children. However, a normal AG doesn’t rule out lactic acidosis, especially in the early stages or in cases of mixed acid-base disorders. This is often seen in compensated shock where the body is still compensating, or in situations where the AG is being lowered by other factors (e.g., hypoalbuminemia or hyperchloremia).

Inborn Errors of Metabolism (IEMs)

Inborn errors of metabolism are a key consideration in children, especially infants, with unexplained HAGMA. Unlike adults, where a high AG is often due to acquired conditions like shock, DKA, or toxin ingestion, IEMs are a significant cause in the pediatric population.

Toxin Ingestion

When considering toxin ingestion, a normal AG can also be misleading. Some toxic ingestions, like methanol or ethylene glycol, may initially present with a normal AG because their toxic metabolites (which cause the AG to rise) have not yet been produced. A high “osmolal gap” in conjunction with a normal AG can be an early clue to these poisonings.