Cranial Nerve Examination in Children

Examining cranial nerves in children requires a different approach than in adults, as their level of cooperation varies significantly with age and developmental stage.

The focus should be on observation and play-based techniques to gain as much information as possible without causing distress.

General Principles

Context is Key: Before starting, understand the reason for the examination. Are you screening a well child, investigating specific symptoms, or assessing a severely unwell child?

Age-Appropriate Approach: Use toys and a playful manner to engage the child. Many parts of the exam can be observed during a normal interaction.

Observation: A significant amount of information can be gathered by simply observing the child’s face, movements, and expressions.

Collaboration: The exam is often done with the parent present, who can provide crucial information on the child’s baseline behaviour and development.

The Cranial Nerves

CN I (Olfactory Nerve)

Function: Smell.

Examination: Testing smell is rarely performed in young children as it is unreliable. In an older, cooperative child, a non-irritating substance like a familiar food or soap can be used.

CN II (Optic Nerve)

Function: Vision.

Examination:

Visual Acuity: Use age-appropriate charts. For a toddler, this might be a “picture chart” or matching games. For a school-aged child, a Snellen chart can be used. In a non-cooperative infant, observe if they track a parent’s face or a brightly coloured toy.

Visual Fields: This can be a game. A child might follow a toy from the periphery into their field of vision.

Pupil Reflexes: Observe the pupils’ reaction to a light source. Note the direct and consensual light reflexes.

Fundoscopy: This is often the most difficult part. It should be attempted last, and a senior colleague should be asked to help if needed.

CN III, IV, VI (Oculomotor, Trochlear, Abducens Nerves)

Function: Eye movements.

Examination: Observe spontaneous eye movements while the child is playing. Use a toy to get them to follow.

Oculomotor (III): Look for ptosis (drooping eyelid) or an eye that is deviated “down and out.”

Trochlear (IV): A palsy of this nerve is rare. It can present with a head tilt to compensate for double vision.

Abducens (VI): The eye is unable to move outwards (abduct). This can be a sign of raised intracranial pressure.

CN V (Trigeminal Nerve)

Function: Facial sensation and mastication.

Examination:

Sensory: This is difficult to test formally. Observing the child’s reaction to touch on the forehead, cheek, and jaw can provide clues.

Motor: Ask the child to clench their teeth while you feel the masseter muscles.

CN VII (Facial Nerve)

Function: Facial movements.

Examination: This can be tested well through observation.

Observe: Look for symmetry in facial movements when the child smiles, cries, or makes faces.

Test: Ask an older child to puff out their cheeks or raise their eyebrows.

CN VIII (Vestibulocochlear Nerve)

Function: Hearing and balance.

Examination:

Hearing: A whisper test or a noise-making toy can be used. In an infant, observe for a startle reflex to a loud noise.

Balance: Observe the child’s gait and balance. Ask an older child to stand on one leg.

CN IX, X (Glossopharyngeal, Vagus Nerves)

Function: Swallowing and gag reflex.

Examination:

Swallowing: Observe the child drinking from a cup.

Palate: Ask the child to say “aah” and observe for the symmetrical rise of the uvula. The uvula deviates to the normal side if there is a problem.

Gag Reflex: Avoid testing the gag reflex unless there is a specific concern, as it is distressing.

CN XI (Accessory Nerve)

Function: Neck and shoulder movements.

Examination: Ask the child to shrug their shoulders or turn their head against resistance, or simply watch them play and move their head freely.

CN XII (Hypoglossal Nerve)

Function: Tongue movements.

Examination: Ask the child to stick their tongue out and move it from side to side. A lesion of the hypoglossal nerve causes the tongue to deviate to the affected side.

Peripheral Nervous System Examination in Children

A neurological examination in children, particularly of the peripheral nervous system, is often challenging due to a child’s limited ability to cooperate. The key to a successful examination is a systematic approach that relies heavily on observation and age-appropriate play, rather than a rigid, adult-style sequence.

General Principles

Observation First: The majority of the neurological exam can be completed by simply observing the child playing, walking, or interacting with their parents. This provides invaluable information on their spontaneous movements, gait, and overall tone.

Context is Crucial: Always be aware of the reason for the examination. Are you investigating a specific symptom like a limp, or are you performing a routine developmental check?

Be Playful: Use toys, games, and distraction to make the examination a fun experience, which will yield better results.

Key Components of the Examination

1. Inspection

Resting Posture and Movement: Observe the child’s posture at rest. Look for any unusual postures, such as a “frog-like” posture in an infant, which can suggest hypotonia. Note if their movements are smooth and symmetrical.

Muscle Bulk: Look for any asymmetry in muscle size or wasting of the small hand muscles. In conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy, there may be hypertrophy of the calf muscles.

Involuntary Movements: Observe for any tremors, tics, or fasciculations (fine muscle twitches).

2. Tone

Tone is the muscle’s resistance to passive movement.

Infants:

“Rag doll” feel: An infant with significant hypotonia may feel like a rag doll when handled.

Pull-to-sit: A child with poor head control will have a significant head lag when pulled to a sitting position.

Ventral Suspension: When held face down, the child should be able to raise their head.

Older Children: Check for spasticity (increased tone that resists a fast stretch) or rigidity (increased tone throughout the range of movement, often seen as cogwheel rigidity).

3. Power

Assessing power is best done through a game.

Infants: Observe the child’s spontaneous movements and their ability to kick or lift their arms against gravity.

Older Children:

Upper Limbs: Ask the child to “give me a hug” to test shoulder power, or “make a muscle” to test elbow flexion.

Lower Limbs: Ask the child to “stand on one leg” or “jump up and down.”

Grading: Use the standard Medical Research Council (MRC) scale from 0 (no movement) to 5 (full power against resistance).

4. Deep Tendon Reflexes (DTRs)

Technique: A reflex hammer can be intimidating. A playful approach is needed. Ensure the child is relaxed, and the limb is supported. The key reflexes to elicit are:

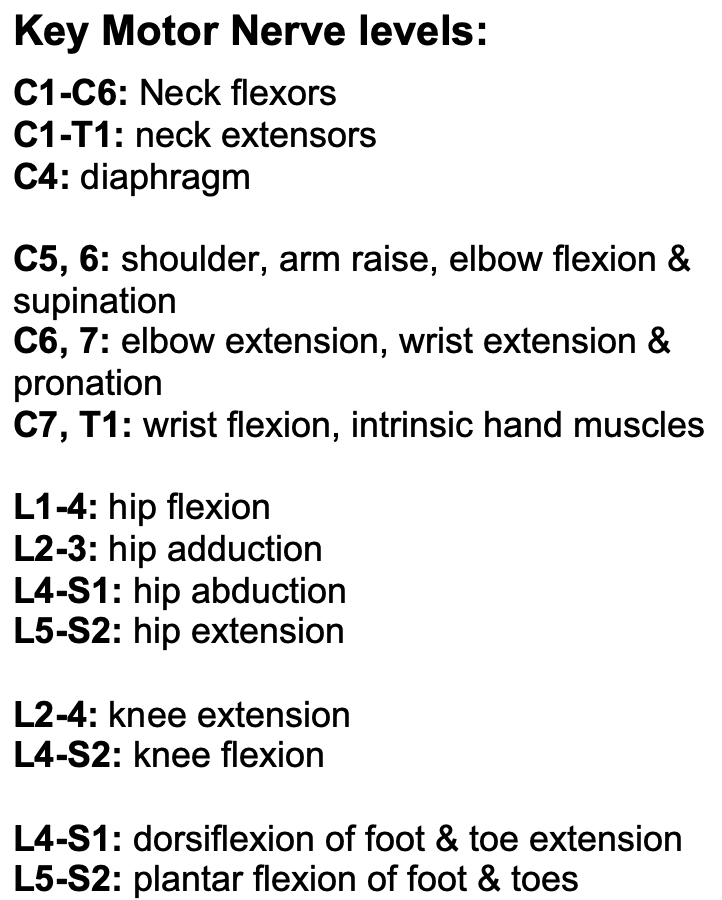

Biceps (C5)

Knee (L4)

Ankle (S1)

Babinski Reflex: The plantar reflex should be tested. In an infant, a plantar reflex is normally “upgoing” (dorsiflexion of the big toe) until around 12-18 months of age. In older children and adults, an upgoing Babinski is pathological.

5. Sensation

Testing sensation is difficult in young children and is often unreliable.

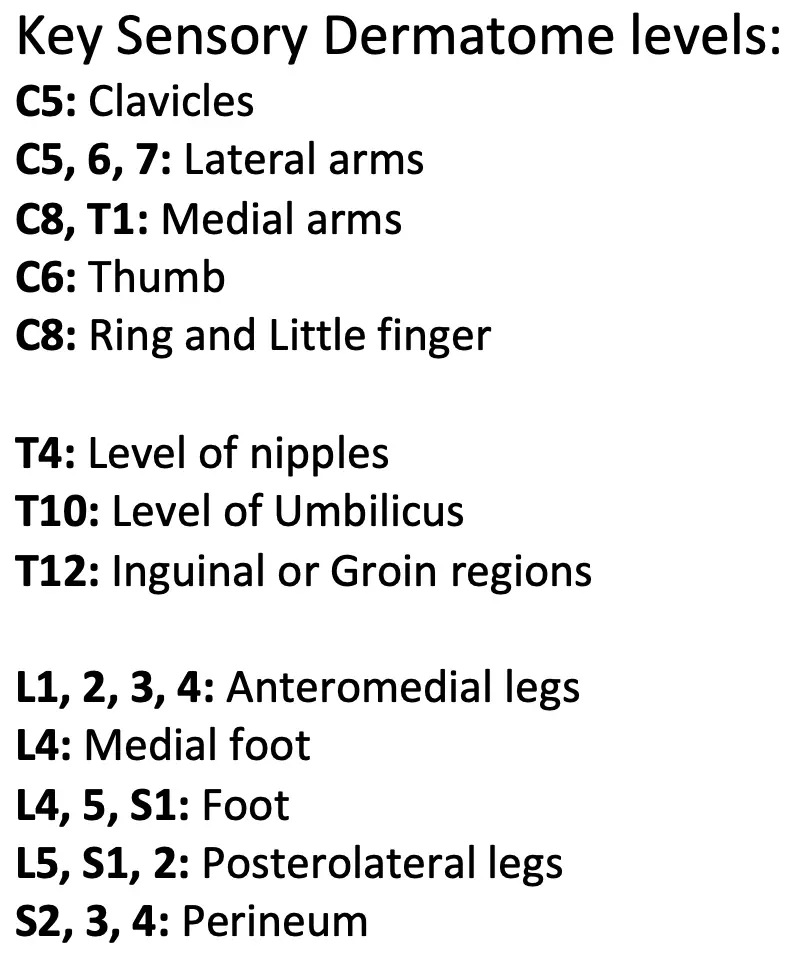

Light Touch: A wisp of cotton can be used to elicit a response.

Pain: A pinprick should be avoided. A gentle pinch may be used, but this is often not needed.

Temperature and Vibration: These are rarely tested in young children.

Coordination and Cerebellar Examination in Children

Examining a child’s coordination is essential when investigating neurological symptoms such as clumsiness, poor balance, or speech difficulties. The cerebellum, a key part of the brain, is responsible for coordinating voluntary movements and maintaining balance. The examination in children is largely based on observation, as many formal tests can be too difficult for them to perform.

General Principles

Context is Everything: The examination approach depends on the clinical context. Is the child presenting with an acute onset of symptoms (e.g., post-viral cerebellitis) or chronic difficulties (e.g., developmental coordination disorder)?

Be Playful and Observational: The best way to assess a child’s coordination is through play. Observe them as they run, play games, or draw.

Involve Parents: A parent can provide a valuable baseline on the child’s typical abilities and developmental milestones.

Key Components of the Examination

1. Inspection

Spontaneous Movements: Observe the child’s posture and how they move. Are their movements smooth and purposeful, or are they clumsy and uncoordinated?

Involuntary Movements: Look for any tremors. An intention tremor, which is a tremor that gets worse as the hand approaches a target, is a classic sign of cerebellar dysfunction.

2. Gait

The child’s gait provides a wealth of information about their motor function and coordination. Ask the child to walk barefoot in a straight line.

Stance and Swing: Observe the symmetry and rhythm of their walking.

Broad-based Gait: A wide, unsteady gait is a classic sign of cerebellar ataxia.

Tandem Walking: Ask an older child to walk heel-to-toe along a straight line. This is a sensitive test for subtle cerebellar signs.

Gait Variations: Be aware of other types of abnormal gait:

Waddling gait: Suggests proximal muscle weakness (e.g., in muscular dystrophy).

Foot drop: Can be a sign of peripheral nerve damage.

3. Balance

Romberg’s Test: Ask the child to stand with their feet together.

Positive Romberg’s: They are unsteady with their eyes closed but stable with them open. This suggests a problem with proprioception (sensory ataxia), not the cerebellum.

Cerebellar Ataxia: They will be unsteady with both their eyes open and closed, as their balance is not dependent on vision.

4. Cerebellar Tests: Upper Limbs

Finger-to-Nose Test: Ask the child to touch their nose and then your finger. This tests for past-pointing (overshooting the target) and intention tremor.

Dysdiadochokinesia: This is the inability to perform rapid, alternating movements. Ask the child to rapidly tap the back of one hand with the palm of the other.

5. Cerebellar Tests: Lower Limbs

Heel-to-Shin Test: With the child lying down, ask them to place their heel on the opposite knee and slide it smoothly down the shin. A clumsy or jerky movement is a positive sign.

Standing on One Leg: This is another test of balance that is appropriate for older children.

Summary and Documentation

The findings should be clearly documented, noting whether any of the observed signs are present and if they are consistent with a cerebellar or other neurological problem. Remember that a normal examination does not rule out a subtle, underlying issue, and a period of observation may be necessary.